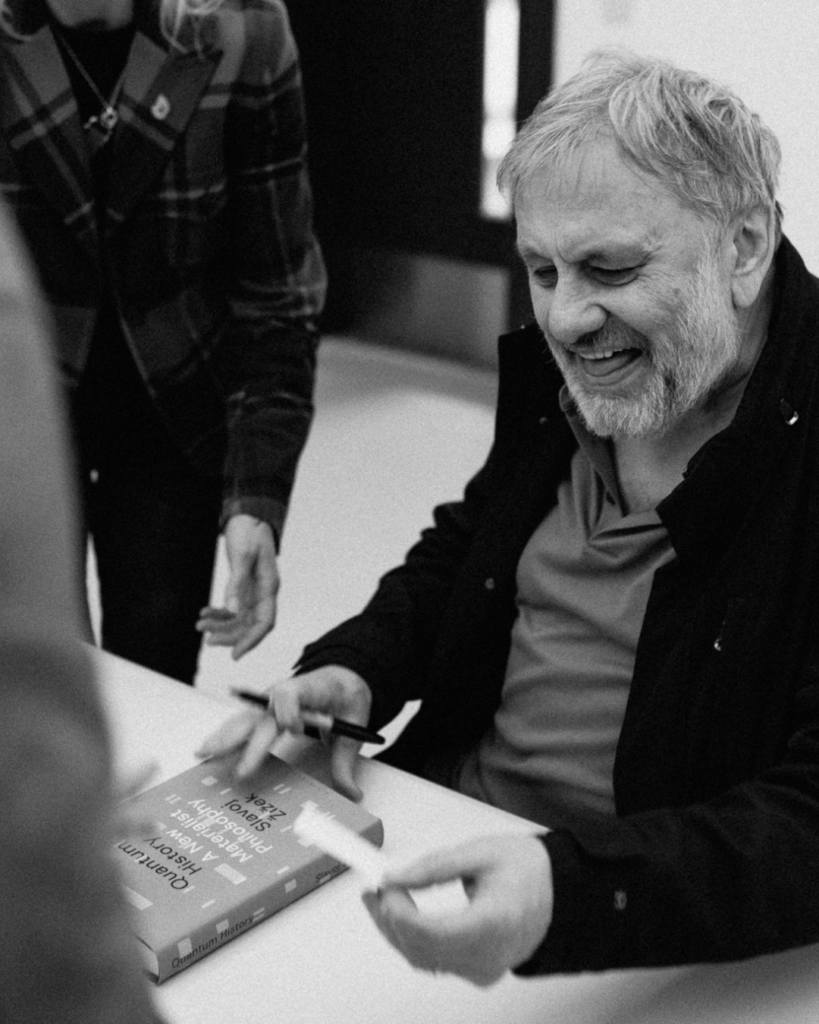

Slavoj Žižek x Emily Adlam: Continental Philosophy Meets Quantum Theory

Philosopher Slavoj Žižek and quantum theorist Emily Adlam explored materialism, the measurement problem, and the radical possibility that reality itself is fundamentally incomplete. Moderated by David Malone, the conversation examined how quantum mechanics challenges our understanding of observation, intersubjectivity, and whether the universe permits any view from nowhere.

By Aaron Shefras

Quantum mechanics and Hegelian philosophy don’t often share a stage, but when they do, the room fills quickly. One evening at Town Hall brought exactly this collision: Slavoj Žižek, whose philosophical provocations arrive in rapid bursts punctuated by tugs at his shirt, and Emily Adlam, a quantum theorist whose writing manages to make the measurement problem feel almost approachable, sitting down to wrestle with materialism, observation, and the unsettling possibility that reality itself might be fundamentally incomplete.

David Malone, the evening’s moderator, set the scene perfectly. He’d made it through Žižek’s book, then picked up Adlam’s and thought, “oh my God, I need a cup of tea.” The room laughed, but it was the kind of laughter that comes from recognition. These are not easy thinkers.

The Trouble with Materialism

The conversation opened on materialism, and specifically on why it’s in trouble. Adlam began with the version sometimes called physicalism, the idea that everything is physical, that we can explain everything without recourse to consciousness or anything beyond the material world. Quantum mechanics, she argued, has repeatedly threatened this view not because it proves materialism wrong, but because it undermines our traditional beliefs about what physical things should be like. The typical responses have been either to abandon physicalism entirely or to try to “fix” quantum mechanics by making it look more classical. Both, she believes, are wrong.

Žižek came at it differently. He spoke of “materialism without matter,” rejecting the reductionist fantasy that ultimately there’s just empty space and small particles hitting each other. For him, materialism means something stranger: we do not have access to any general, total view of the universe. Every universality is rooted in a singularity, from a particular point. He invoked Marx, not the teleological Marx marching inevitably toward capitalism, but the Marx who said capitalism is totally contingent, yet once it emerges, it becomes necessary and we read all the past from it.

This twisted, cracked structure, this impossibility of a universal view, this is materialism for Žižek. He cited the wonderful paradox of temporal lending in quantum mechanics, how a photon can borrow energy from the future and repay it before observation. Retroactivity. Contingency collapsing into necessity. Not irrational, but fundamentally non-linear.

The Problem of the Observer

Both thinkers circled repeatedly around the observer, that troublesome presence at the heart of quantum mechanics. Traditionally, science has expected that observers can be mostly left out of our descriptions. The world is there, doing its thing, and the observer comes along and looks but plays no significant role. Quantum mechanics makes this impossible. The theory, as currently formulated, requires an observer to make sense of it.

Žižek agreed, but from the opposite direction. The role of the observer is not idealism, he insisted, it’s the opposite. We are engaged as observers because we are part of reality. The neutral materialist view from some divine position observing the world, that’s what he rejects.

Some interpretations lead to what Adlam calls “Type 3 Discord,” where when one person makes an observation and tries to communicate it to another, what the second person hears may not match what the first intended to say. The glass is over there becomes lemons grow on trees. This is where Adlam draws her line. Such interpretations undermine the social process of science itself, the sharing of results, the peer critique, the collective validation that makes science possible. If my mind cannot connect with yours, if there’s no intersubjective space, then science as we know it collapses.

Weirdness, Benign and Epistemic

Toward the end, Adlam introduced a crucial distinction. Quantum mechanics is weird, everyone agrees on that. But there are different types of weirdness. Benign weirdness offends our classical sensibilities but doesn’t break our scientific methodologies. Epistemic weirdness is more dangerous because it undermines our means of inquiry, our means of learning about the world.

As Malone pointed out, it’s paradoxical: the practice of doing experiments led us to quantum mechanics, which then tells us we can’t trust the experiments that led us there. A theory that undermines the evidence used to establish it.

Žižek brought it back to incompleteness. For him, the shock of quantum mechanics is encountering imperfection and inconsistency in nature and recognizing it as ontological, not epistemological. It’s not that our knowledge is incomplete, it’s that reality itself is incomplete. This radical openness, this gap in being, is precisely what quantum mechanics reveals.

Adlam doesn’t disagree. Quantum mechanics is telling us something substantive about ontological gaps. But any solution to the measurement problem needs to account for the fact that measurement plays a central role in establishing our picture of the world. The ontological answer must meet the epistemic challenges.

Someone from the audience asked if simulation theory could explain the weirdness. Žižek’s response was characteristically contrarian: he suspects simulation theories precisely because they offer an escape from truth, and for him, truth always returns, you cannot escape it.

The conversation sprawled across philosophy and physics, consciousness and matter, Hegel and Heisenberg, but what made it work was the space itself. Town Hall doesn’t flatten difficult ideas into digestible sound bites. It creates room for complexity, for disagreement, for the kind of intellectual exchange that requires you to lean forward in your seat and follow the thread even when it tangles. This is what the venue was built for: not answers, but the shared effort of asking better questions. Two thinkers, one stage, an audience willing to sit with uncertainty. That’s the real quantum state, uncollapsed and alive with possibility.